I just finished watching Secrets We Keep, a Nordic mystery thriller on Netflix set in the affluent North Zealand in Denmark. The story begins with the disappearance of a young Filipino au pair, Ruby, and follows Cécilie, a neighbour who becomes convinced something terrible has happened. As she starts asking questions, she not only uncovers what happened to Ruby but also begins to see the cracks in her own life, her marriage, her privilege, her “good person” image.

It’s a gripping series on the surface…the kind of slow-burn, moody Nordic storytelling that builds tension through quiet moments and cold light. But what stayed with me wasn’t the mystery. It was what lay beneath it: class, invisibility, and the convenient moral blindness that keeps certain lives running smoothly at the expense of others.

After watching the show, I started reading about Denmark’s au pair culture, which, in theory, is a program built on cultural exchange. Young people, mostly women, live with host families, help with childcare and light chores, and in return get room, board, and a small allowance. On paper, it’s meant to be a way to experience Danish culture and learn the language. In reality, it often drifts into exploitation. Many au pairs, particularly from the Philippines, report working long hours, being asked to perform full-time domestic work, and facing emotional or financial manipulation.

It reminded me of one line from the show that cut deep. When Cécilie decides to fire her au pair, Angel, she says she wants to “spend more time with her son” after all that’s happened with Ruby. Angel replies quietly, “You have no idea about my reality.”

That sentence, so simple, so devastating, could have been spoken by countless women across the world who live and work inside homes that aren’t their own, in countries that aren’t their own…

There’s a moment in the series where Cécilie’s colleagues accuse her of having a colonial mindset. At first, it feels like an academic insult, the kind of critique you hear in a university seminar. But the more I watched, the more I saw how painfully accurate it was.

Cécilie wants to “help.” She’s kind to the au pairs. She asks questions. But she never listens. Her empathy is self-centred…a way to soothe her guilt rather than truly understand another person’s life.

It’s the same pattern we see in so many privileged contexts – the “good” employer who thinks being friendly or generous cancels out the power imbalance. The same people who’ll say “we treat her like family” about their maid, while never actually thinking about what her life outside their home looks like.

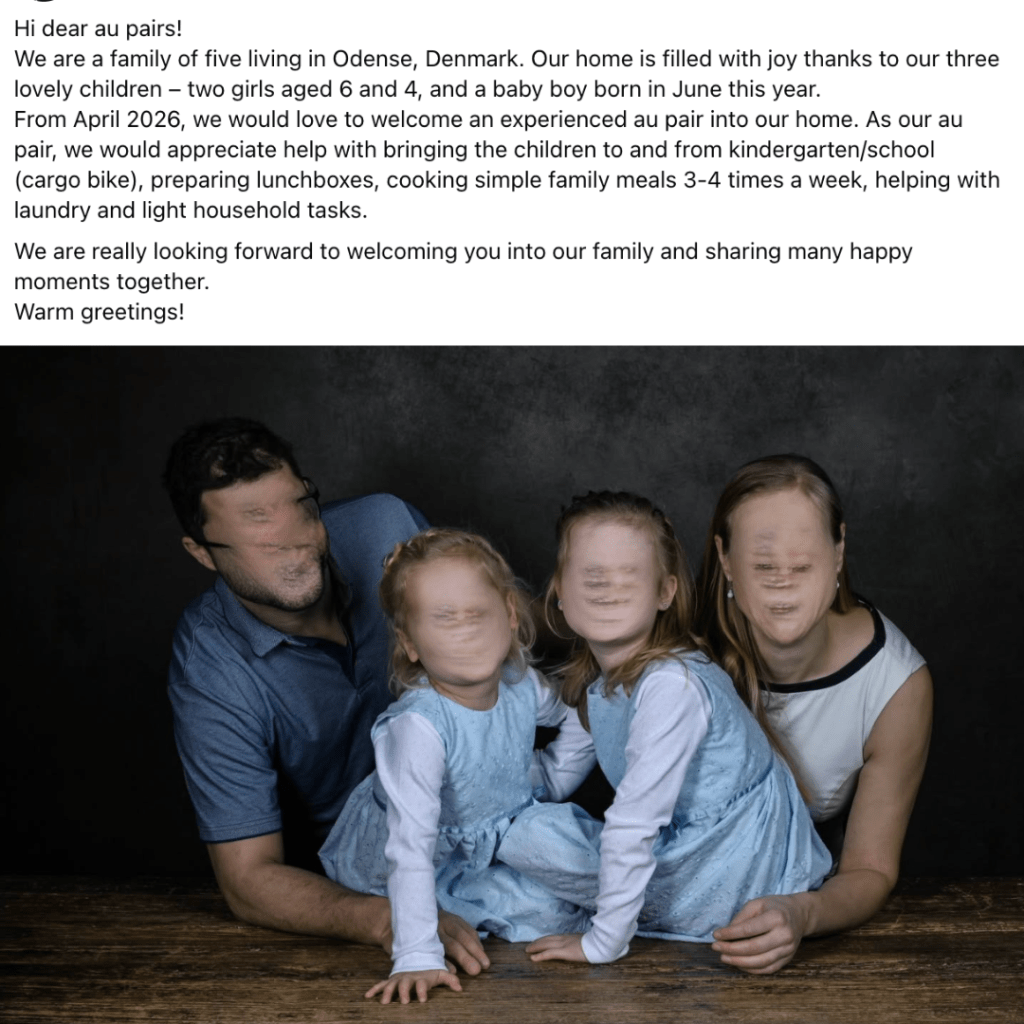

During my research, I came across a recent Facebook post from a Danish family looking for an au pair — a smiling couple with two blue-eyed daughters in pastel dresses, announcing that their home “is filled with joy” and they “can’t wait to welcome an experienced au pair” to help with school runs, meals, and laundry.

There is nothing really wrong in the post. The tone is cheerful, almost innocent, yet the image of the picture-perfect white family radiating comfort and warmth gave me the heebie-jeebies. Because once you’ve looked behind the curtain, it’s impossible not to see the imbalance coded in that “invitation.”

The real reason why I was left deeply unsettled by the show though, wasn’t just this subtext of class disparity and imbalance. Watching the show took me right back to India, to the quiet backrooms of upper-middle-class homes, where full-time domestic workers live. Most of them are women from poor rural backgrounds, or from neighbouring countries like Nepal. They cook, clean, care for children, and sleep in tiny quarters, often without days off or proper contracts.

I’ve seen this equation play out my whole life – the illusion of closeness between employer and worker, the blurry line between affection and ownership. There’s always that unspoken hierarchy, that “as long as she knows her place” attitude, wrapped in politeness.

And this isn’t a distant, abstract problem. It’s right here, earlier visible in the cities of North India, and now increasingly so in Bangalore as well. In many of the city’s upscale apartment complexes, you see live-in maids from Nepal, Jharkhand, Assam — working around the clock, their lives revolving entirely around the homes they serve. The story is the same: a kind employer, a “safe home,” and a salary that goes back to a village they may never truly return to. It’s a form of dependency that feels modern on the surface but is, at its core, feudal.

In many cases, the salaries are sent directly to families back home — which sounds responsible until you realise it also traps them. If they’re fired suddenly, they’re left with nothing. No savings, no network, no safety. Some end up destitute in cities. Others return to poverty or abusive situations they once escaped.

They live in limbo — visible, yet unseen. Essential, yet dispensable.

What struck me most about Secrets We Keep was that it held up a mirror…not just to Denmark, but to all of us who live in societies that run on invisible labour. The nanny, the driver, the cleaner, the security guard – people whose work allows us to live comfortably, but whose humanity we rarely acknowledge beyond a surface gesture.

We build entire lifestyles around other people’s limited choices and call it normal.

And yet, these dynamics continue precisely because they’re so ordinary. Because the stories we tell ourselves about being good employers, or about “helping them” are comforting. They allow us to look away.

In the end, Secrets We Keep isn’t just about Ruby’s disappearance. It’s about the secrets that allow such disappearances, literal and metaphorical, to happen every day. The silence around exploitation, the hierarchy we justify with kindness, the blindness that privilege brings.

Cécilie’s final realisation that she’s been part of a system she thought she was above is one many of us would resist making. But maybe that’s the point.

Because the next time we accuse someone of having a “coloniser’s mindset,” maybe we should stop and reflect on our own. The truth is, real decolonisation doesn’t happen in theoretical, aatel (intellectual) conversations. It begins with everyday liberation – the kind that comes from examining how we treat those who depend on us, how we use our privilege, and what we choose not to see.

The secrets we keep are rarely about others. More often, they’re the ones we hide from ourselves.

Leave a comment