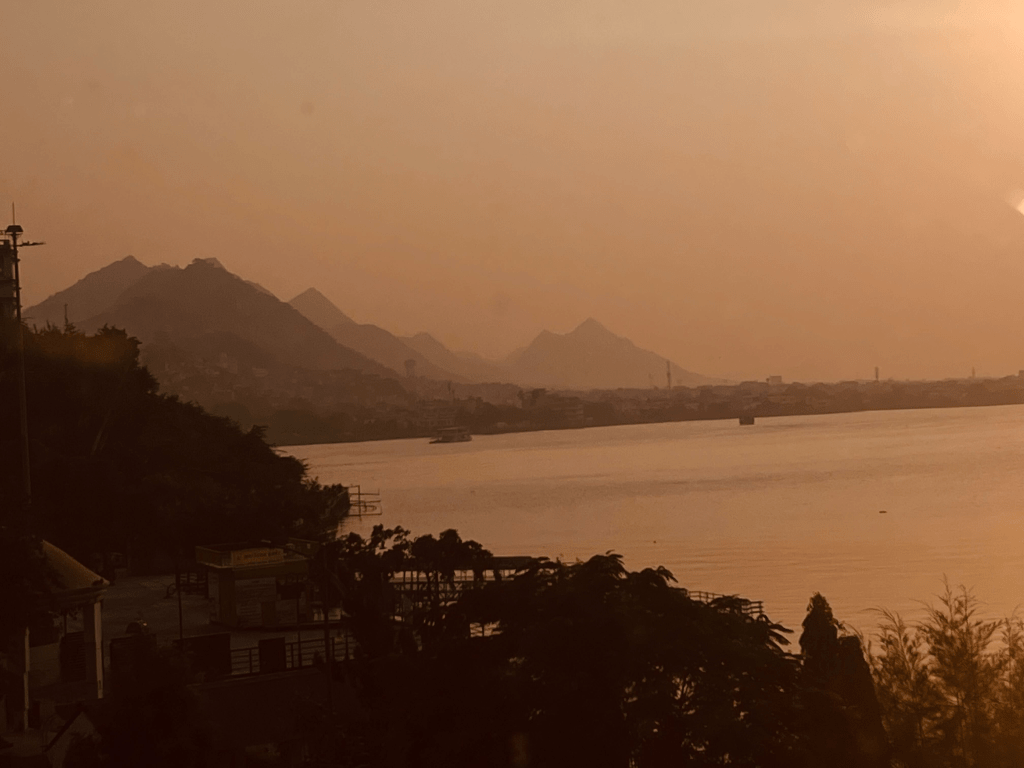

Over the past few days, I have been in Ajmer, spending time at Adaptiv’s newly set-up AI Lab. The office is right on the edge of the Ana Sagar lake, and the setting added a kind of quiet focus that is hard to find in most work environments. Between long strategy sessions with Titash on the future of Adaptiv, the role of the AI Lab, and the next steps for Ask Sétu, I found myself repeatedly drawn to the lake outside the window.

The lake is hard to ignore. Ana Sagar is clean, calm, and surprisingly absorbing. At different points of the day, the water changes in colour; the activity on the lake shifts; the quality of light moves. My eyes kept returning to the surface – sometimes to follow the movement of the many migratory and local birds landing on the lake, sometimes a passing boat, sometimes to watch the stillness, and sometimes nothing in particular, just the surface of the water moving on its own time…

One of the things that stood out was the range of activities on the lake. There are several cruise options, including the recently launched e-cruise, which glides across the water with barely any noise. And then there was something even more striking: a water-cleaning boat making its steady rounds.

I had first seen such a boat in Canal de l’Ourcq in Pantin, near Paris. At the time, I remember admiring the French local authorities for their commitment to maintaining public spaces…not just the major tourist areas, but the everyday neighbourhood spaces that residents interact with. Seeing a similar initiative in Ajmer felt unexpectedly reassuring. It reminded me that civic responsibility doesn’t have to be a rare exception in India. When implemented well, it can become a visible, everyday part of life.

It also reminded me how conditioned many of us are to not expect such things in India. A clean lake, well-maintained surroundings, environmentally conscious recreational activities, and regular public-space maintenance are things we tend to associate with cities abroad. The Ana Sagar experience challenges that assumption. It shows that these standards are not only possible in India, they already exist in some places.

As I spent more time by the window, another thought surfaced: pride in one’s city. I have felt this before, as an outsider. In Grenoble and Pantin (neither of which were “home” for a very long time), I still felt a sense of pride simply because I lived there briefly, explored the neighbourhoods, and saw how much care had gone into their public spaces. And now, as an outsider again, one who will likely visit Ajmer frequently, I have started feeling a similar stirring of admiration and pride here too, and hoping that Adaptiv’s AI Lab will become a small part of this pride, adding its own momentum to the city and helping Ajmer scale new heights in the years ahead.

Interestingly, when I spoke to people locally, very few seemed to notice or feel the need to discuss the lake, and how it has been rejuvenated over the last few years. Perhaps when something becomes familiar, it becomes invisible. But I couldn’t help thinking about how small recognitions like this matter. Admiration, however quiet, can create its own kind of encouragement. Local bodies, like anyone else, respond to the feeling that their work is seen.

The contrast with other cities made this even more apparent. My mind went back to the other lakes I’ve frequented (Ulsoor Lake in Bangalore, and Pashan Lake in Pune) – places that could have been just as beautiful and lively. In both cases, I used to once go for walks around the lake, or just go there to soak in the peace and quiet surrounded by nature. But over time, neglect lead to the spaces becoming cluttered with garbage, and the growing blanket of water hyacinth made the lake itself difficult to enjoy. Eventually, as the neglect grew, those spaces started becoming unpleasant, and I had to stopped going there.

Both these lakes have the potential to be exactly what Ana Sagar is today: a shared civic space that brings people together, encourages small businesses, supports local tourism, protects the and gives residents a sense of pride. Instead, it has become a reminder of what happens when maintenance, community involvement, and governance no longer move in sync.

Watching Ana Sagar each day made this contrast sharper. There is a sense of quiet consistency in the activities. Nothing feels dramatic or staged. The cruises are running. The maintenance boat is doing its job. The lake looks well cared for. People walk by, sit on the benches, chatting, taking photos, or simply looking out at the water.

It feels natural, unforced, and part of the city’s rhythm. It reminded me of the possibilities that open up when public spaces are cared for consistently. It also made me reflect on the role that community pride plays in sustaining them. Good urban spaces are not a luxury. They are central to the wellbeing of a city. And examples like Ana Sagar offer a blueprint worth studying, replicating, and celebrating.

Leave a comment